Will Tuttle on Circles of Compassion: Connecting Issues of Justice

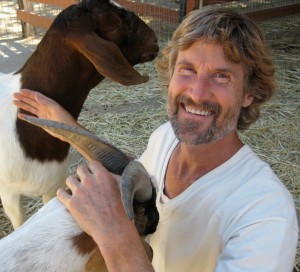

Few living vegans are as influential and as compelling as Dr. Will Tuttle. His book The World Peace Diet has been called one of the most important books of the 21st century, and many vegans and activists credit Will with sparking their initial (or eventual) shift to veganism. Will and his wife, artist Madeleine Tuttle, travel the world giving lectures, workshops, and trainings based on The World Peace Diet, including veganism, spirituality, effective activism, and personal development.

Few living vegans are as influential and as compelling as Dr. Will Tuttle. His book The World Peace Diet has been called one of the most important books of the 21st century, and many vegans and activists credit Will with sparking their initial (or eventual) shift to veganism. Will and his wife, artist Madeleine Tuttle, travel the world giving lectures, workshops, and trainings based on The World Peace Diet, including veganism, spirituality, effective activism, and personal development.

Will is a former Zen monk with a master’s in humanities and a PhD in philosophy of education, and his work is embedded with these twin threads of spiritual consciousness and intellectual examination. Now, he is assembling the works of 28 other authors for Circles of Compassion: Connecting Issues of Justice, due out this July from the innovative new company Vegan Publishers. The writers explore the connections between injustice to animals and other social and ecological injustices.

From Will:

“Too often, we fail to recognize how forms of violence and oppression are connected. If we’re able to see and understand these connections, we can better leverage our collective efforts to bring about positive transformative change. We’ve put together a book of essays from leading activists who work to end different forms of violence to help lead us to that path. The book could be the push that we need to break out of our confining delusions, to build bridges between movements, and to make the choices that will lead to a peaceful and just world for all.”

I spoke with Will about the new book and his work.

What inspired you to put together Circles of Compassion: Connecting Issues of Justice? Is it unusual for you to be on the editorial side of a project rather than the side of the creator, composer, artist?

I was originally asked to contribute an essay for a book that was to be titled Connect the Dots, which was to be published by Vegan Publishers in Massachusetts. When it became clear that the book also needed an editor, I enthusiastically responded because the essential message of the book is in complete alignment with my work in vegan advocacy, and with the message of The World Peace Diet.

Being an editor is quite a bit different from being the sole creator of a book and requires a different attitude and way of working. The interesting thing is that it’s not really unusual for me, even though I’m primarily known as an author and lecturer. That’s because of two things. One is that as a vegan educator, I’ve created and continually present both in-person and online vegan advocacy trainings that use not only my own writings, but also supplemental readings written by other researchers and authors in a variety of fields that are relevant. As an active member of the vegan movement for more than thirty years now, I’m keenly aware that none of us operates in isolation. We are all are embedded in an ongoing cultural conversation and ever-unfolding evolution of understanding that we co-create together by sharing ideas and building off of each others’ work.

The other is that I was born and raised as the oldest child in a newspaper family and from a young age was trained as an editor. In high school I was filling in for newspaper editors in my father’s chain of newspapers in Massachusetts, and in college, I worked as a copy editor part-time for the local daily in Waterville, Maine. So being an editor is natural and comfortable for me, even more than writing in many ways. A good writer needs also to be a good editor because it’s such an important part of presenting one’s ideas to the world. I’m used to spending a lot of time and energy honing the verbalization of ideas, which I find to be an enormously helpful and illuminating (albeit sometimes frustrating!) exercise.

Your work has always made the connection between eating and using animals and other social justice issues. Why do you believe there’s such a disconnect between social justice activists and eating and using animals?

That’s an essential question. The most obvious and main reason is that these very social justice activists you speak of are, like the vast majority of people in our culture, purchasing and using animal-sourced foods and other products on a daily basis. This is not only supremely ironic; it is unfortunately catastrophic also.

This is because the relentless and unconscious abuse of nonhuman animals is rampant in virtually all forms of social activism, and this decreases effectiveness and basically guarantees that little progress will be made. In paying for and eating animal-sourced products, we are voting for and literally consuming the exact opposite of the peace, justice, sustainability, equality, freedom, and compassion that we are, in our minds, working and fighting for. We don’t realize that by failing to question the core routine violence in our culture—toward animals for food—we are desensitizing ourselves and rendering our efforts merely ironic.

This is not true just for social justice advocates, by the way. It’s also true for those who are working for spiritual awakening as well. The disconnect in both activists and spiritual aspirants that we’re discussing similarly hampers their efforts, and the core teaching of veganism provides the key missing element, which is to be radically inclusive in our approach to compassion and justice.

What do you hope readers will take away from the book?

That’s an intriguing question, because there are so many different takeaways in this book, and so I think it will depend a lot on the individual readers. All of the authors are vegan and bring the vegan perspective to their activism, research, and writing, and they are all involved in more than just vegan advocacy. Some work with social justice issues like racism, sexism, ableism, and heterosexism. Others work in the fields of economic disparity, hunger, poverty, peace and conflict studies, and classism. And others work in the areas of environmental justice, sustainability, and agriculture.

For me, as the editor, reading the essays was enlightening, refreshing, and empowering. The media conversations are filled with a constant stream of information about our various problems and crises, and the role of animal agriculture and the mentality of exploitation that animal agriculture engenders in all of us is typically completely ignored. So for me, having an entire volume of diverse and highly knowledgeable voices all explicitly including this missing and essential perspective makes this book a gold mine, not just of important insights, but also of specific practices that can help build a new wave of social justice movements. There are stories and examples that can help readers not just to understand the intersections of the justice movements more clearly, but also inspire them to take action in more effective and creative ways. Plus, the quality of the ideas shared by the authors is superb, which makes reading the book a rewarding educational experience in and of itself.

While many people working for social justice causes may not know about the violence inherent in animal foods, many others do know and don’t make a change. Any thoughts on why someone who clearly expresses compassion and justice towards one issue may not seem to care about other animals?

This question gets to the heart of our cultural situation, and the crucial operative word here is “know.” What does it mean when we say some activists don’t know about the violence in animal foods and products, and others do know? I would say that paradoxically, the ones who don’t know: they actually do know. The others who know: they actually don’t know.

As to the former, it’s unthinkable that any minimally educated and aware person in our society today doesn’t know about the inherent violence in animal foods; the awareness of this violence is just suppressed, and it has to be continually suppressed, which takes ongoing effort, like the constant effort of holding an inflatable ball under water. By blocking awareness, we can stay comfortable, and we’re supported in this by every institution in our culture, but our effectiveness and intelligence are also unfortunately suppressed.

Regarding the latter, if we know about the violence toward animals and others required by animal-sourced foods and don’t make a change in our behavior because of this, then I would say we don’t actually know about it. There is a pithy saying by Goethe that sums this point very well: “To know and not to do is not to know.” It’s easy in our culture for me to tell myself and others that I understand the food system here and that animals suffer for food, but it’s just part of life feeding on life, or that I just can’t be a vegan because I am a blood type O or some other disempowering rationalization. The vast majority of people in our society, including other activists and aspirants, will support us in these and similar rationalizations.

What I’ve come to realize in my 34 years living as a vegan in this culture is that going vegan is profoundly challenging for most of us because it forces us to realize that our home culture and every institution, even including our family, are relentlessly propagating violence and disconnectedness. This painful realization is ultimately profoundly liberating, however, making veganism like a second birth in many ways. We are forced to leave the comfort of the familiar as our evolving awareness ejects us from the womb of unquestioning loyalty to our inherited food choices. Simultaneously, we are born into a new adventure: a life where we can live at a whole new level of joy, creativity, and freedom from exploiting and exploitation. Make no mistake. Anyone who is not vegan is being exploited. Exploiting others and being exploited are inseparable. Going vegan is the action that is inseparable from knowing, and without this action, there can never be any authentic understanding. We all have our unique journeys both before and after the second vegan birth, and I would say that there are certainly many more challenges ahead of us after going vegan, and further stages of veganism we can attain as our understanding deepens. The beauty of our life here on this Earth is that we can learn from our experiences and from each other, and work together and grow in awareness in our brief and poignant time here.

Next year marks the tenth anniversary of The World Peace Diet. The book is as critical to our understanding of the issues today as it was a decade ago. It is truly essential reading. What accounts for its longevity?

Thank you, Gary, for this interview, and for offering this observation. You’re right: The World Peace Diet seems to be growing in its power and influence every day, every month, and every year. In many ways, it’s an eternal book. There is little in it that I would change if I were to write it today. The principles it elucidates are universal and timeless.

I say these things because in many ways I don’t feel it is “my” book. I became aware back in the late 1990s that an important book needed to be written so that our culture would have a new understanding (based on ancient teachings) that would create a proper foundation for peace, justice, freedom, and harmony in our world. When I realized that I was called to write the book, I did so, but with the sense of volunteering for a sacred mission that was not at all for myself, but for all living beings of all time.

Every year The World Peace Diet is translated into more languages and reaches farther and more deeply into the consciousness of humanity. As it does so, the world is irrevocably changed, because the essential truth is that we are all interconnected on this planet, and our true nature is calling us to awaken from the delusion of essential separateness. The message of The World Peace Diet is carried by every blossom, every blade of grass, every birth, every sunrise, every smile of understanding. We live in a benevolent universe, and we are meant to celebrate our lives here with joy, exuberance, and lovingkindness for all.

The World Peace Diet emphasizes that veganism is a modern iteration of ahimsa (“nonviolence”), the ancient universal core of all spiritual teachings, and veganism’s founder, Donald Watson, spent his last days on Earth at the age of 95, back in 2005, reading The World Peace Diet, and told the people around him that this book contained what he was trying to convey in coining the word vegan. So perhaps The World Peace Diet is Donald’s book!

I see The World Peace Diet as a manifestation of an unstoppable spiritual force that is rooted in our true nature, which is, essentially, wisdom and compassion. It appears as a book that helps remove the cultural blinders, a tool that allows the sun to shine again into the darkness of a world that has been held hostage for too long to indifference and abuse. Its message will, I’m certain, continue to grow and spread, and this new book, Circles of Compassion, is a manifestation of this, bringing a whole chorus of voices to help proclaim and clarify this message for our time.

Please support the book by pre-ordering or contributing to its crowdfunding campaign here: https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/circles-of-compassion-connecting-issues-of-justice#home

Comments

- Racism and Cecil: Making the Connection | Integritus Prime - […] must make the connection, as the recent anthology Circles of Compassion does, between the movements for human rights, black […]

- Circles of Compassion: Essays Connecting Issues of Justice - Humane Decisions - […] Read more about Circles of Compassion by Dr. Will Tuttle on The Thinking Vegan. […]

Leave a Reply

*

Dr. Will Tuttle

April 18, 2019

Re-reading this interview 5 years later, I’d like to again thank Gary Smith for facilitating the opportunity to share these still-relevant ideas, and also apologize if I gave any offense to any readers who might object to my somewhat light-hearted comment in the penultimate paragraph that The World Peace Diet is perhaps Donald Watson’s book. Of course The World Peace Diet is my book and I take full responsibility for all the ideas contained therein.

I was told by a journalist who was visiting with Donald Watson near the end of his life in 2005 when The World Peace Diet was first published that someone was reading it to him daily and that he was enthusiastic in his appreciation of it. I was glad to hear this and am grateful for his enormous contribution to our world in helping to create the modern vegan movement, which, as I discuss in my new book, Buddhism and Veganism, has ancient roots in Asia. Again, my apologies to any who might object for some reason to my sharing of this story about the connection with Donald Watson.

Although I could never meet Mr. Watson in this lifetime except through his ideas, I’m grateful he was able to meet the ideas in The World Peace Diet just before his passing, and that the vegan movement, through the efforts of countless and ever-growing numbers of caring people, is continuing to grow and help transform our world in a positive way.